Working Out the Bugs

Franz Kafka spilled his guts for readers. He exposed his tortured soul in ways that few other writers ever did.

The Heart of My Burrow

"For writing means revealing oneself to excess…"

Management expert Peter Drucker believed that Franz Kafka invented the hard hat construction workers wear. How ironic it would be if that were true (and there is no evidence to prove that it is), because if anyone in human history would have had a safe or a steel girder fall on him, it would have been Kafka, and, of course, the hat would have done him no good.

It should surprise no one that Kafka's work as an insurance claims analyst in Prague often involved investigating claims by worker whose fingers had been scissored off or legs mangled into jelly by industrial accidents.

During his short, unhappy life, Kafka wrote stories and novels that are the quintessence of dread. Misery, shame, claustrophobia, self-loathing, disgust, horror, anguish, fear, anxiety—all describe what one feels when reading his tales of existential meaninglessness.

In some respects, Kafka, who died of tuberculosis at age 40 in 1924, was a coward. He lived most of his life under the same roof as his overbearing, selfish father, suffering in silence in their cramped apartment.

His love life might best be described as excruciatingly excruciating. Engaged to marry three times, he had low self-esteem and feared sexual encounters, once writing that he perceived of "coitus as punishment for the happiness of being together." He also wrote that "The idea of a honeymoon trip fills me with horror." No wonder that a character in Annie Hall says to Woody Allen's character "Sex with you is really a Kafkaesque experience."

Unable to take joy in his creativity, he told his diary, "The story came out of me like a real birth, covered with filth and slime."

"Be quiet, still, and solitary"

He wanted only to be left alone to write—"You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet."

The greatness of Kafka's work comes thanks to his courage—the bravery with which he revealed his tortured soul on paper. One of his friends praised him for his "absolute truthfulness."

As Kafka wrote in his diary "For writing means revealing oneself to excess; that utmost of self-revelation and surrender, in which a human being, when involved with others, would feel he was losing himself, and from which, therefore, he will always shrink as long as he is in his right mind."

Writing was what his lived for, he yet felt writing itself was akin to dying. "My talent for portraying my dreamlike inner life has thrust all other matters into the background," he wrote. "My life has dwindled dreadfully, nor will it cease to dwindle…I waver on the heights; it is not death, alas, but the eternal torments of dying." Yet Kafka also called the hours he spent writing "a form of prayer."

Guilt and punishment obsessed him. The central theme of his works is that individuals, through no fault of their own, must suddenly pay for crimes whose nature is never known. To Kafka, it was as if life itself was a punishment and that brutal chastisement served no purpose and had no meaning.

In Der Process (The Trial), Josef K. is arrested by unknown authorities. Neither he or the reader is never told what crime he has committed. When the story ends, he is stabbed to death. His last words are "Like a dog!"

"A monstrous vermin"

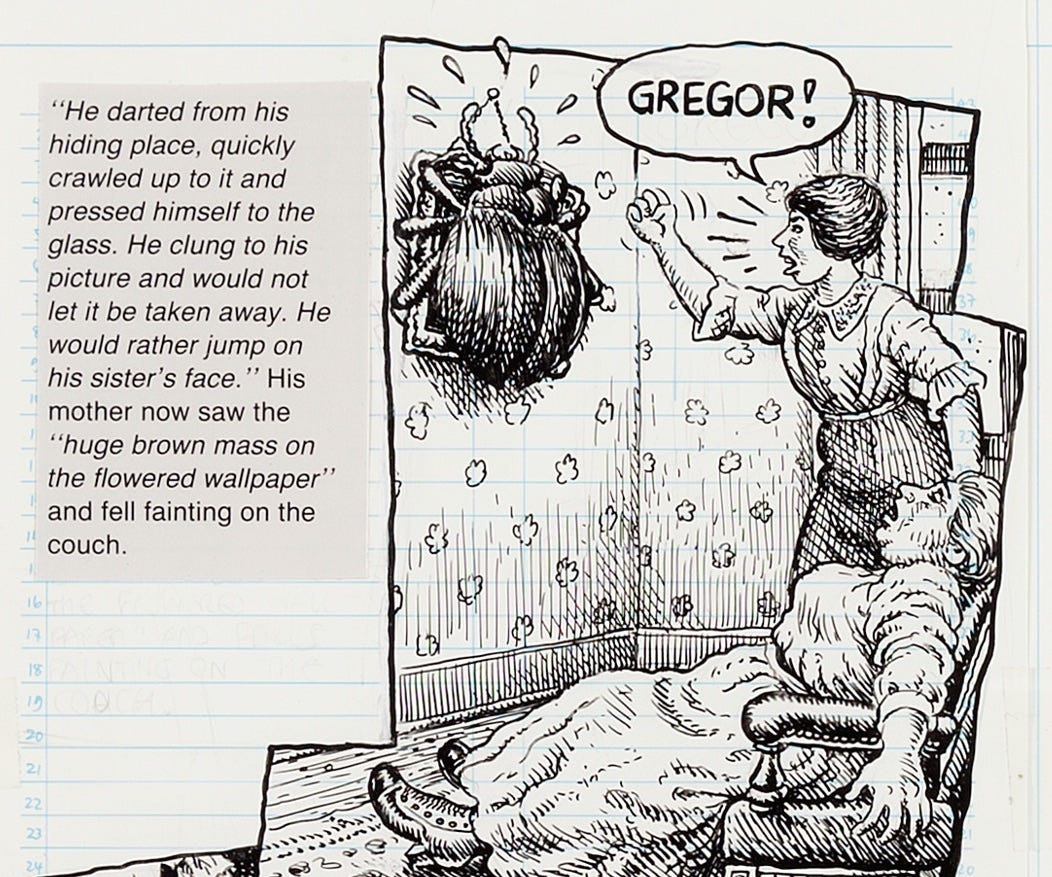

Die Verwandlung (Metamorphosis) begins with the sentence: "When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin." Not necessarily a beetle as is commonly believed but something worse—"a vermin."

Trapped in his room, he disgusts his relatives or is ignored by them, until his father attacks him. "No plea of Gregor's availed, indeed none was understood; however meekly he twisted his head his father only stamped the harder." Finally, his father kills him by hurling apples at him, one of which becomes embedded in his flesh.

In der Strafkolonie (In the Penal Colony) an explorer is shown 'the harrow,' an instrument which embroiders into a prisoner's flesh the text of the rule he has disobeyed.

'My guiding principle is this: guilt is never to be doubted.' The prisoner is never told the nature of his crime," says the officer who runs the machine and who decides to submit himself to it. "There would be no point in announcing it to him. You see, he gets to know it in the flesh."

Although Kafka wrote this story between 1914 and 1919, one sees in it and in many of his other works a foreboding of what was to come in Europe. In Der Bau (The Burrow), he writes of a mole-like creature who dwells in a sealed-off underground labyrinth of tunnels and chambers. "I live in peace in the heart of my burrow, and meanwhile from somewhere or other the enemy is boring his way slowly towards me."

His three sisters Ottla, Valli, and Elli were murdered by the Nazis. All were deported from Czechslovakia to Poland. Elli and Valli died in the Lodz Ghetto, the second largest ghetto the Nazis created in Poland. His favorite sister Ottla was taken to Theresienstadt concentration camp. She volunteered to accompany 1,260 children as part of a "special transport" to Auschwitz where she was killed.

"Man cannot live without a permanent trust in something indestructible within himself," Kafka wrote. "Though both that indestructible something and his own trust in it may remain permanently concealed from him. One of the ways in which this hiddenness can express itself is through faith in a personal god."

MORAL: Life is change, but it doesn’t have to be a..metamorphosis.