“We don’t quit.”

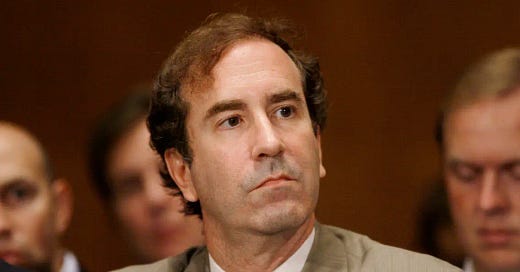

Harry Markopolos’ father owned a chain of 12 Arthur Treacher’s Fish ‘n’ Chips restaurants. As a child, he must have developed a nose for knowing when something smells fishy. When he grew up he became an investment advisor and portfolio manager at a Boston investment company.

In 1999 another money manager at his firm told him about a hedge fund that was earning its luxe clients a steady one to two percent net return on their money every month—month after month, with only a very few monthly exceptions. The question was—should we get our clients in on this action?

To Markopolos, this smelled like week-old haddock in August. After all, when Markopolos was a young man he discovered fraud at his father’s restaurant chain. An employee was stealing cases of frozen fish fingers, and Harry put his thumb down on the not-so-well breaded bandit.

It is impossible for any investment to always return a profit (unless it is something like a bank savings account that has a fixed return). Instantly, Markopolos knew he was looking at a Ponzi scheme.

This type of financial rip-off gets its name from con artist Charles Ponzi who promised investors fantastic returns. He was able to achieve this, for a while by taking money from newcomers and parceling it out to those who got in first on the deal. The only way it works is if the con man has a steady and growing stream of new money coming in.

What Markopolos had stumbled onto was Bernie Madoff’s $65 billion con game serving some of the wealthiest people in the world, likely including the Russian mafia and international drug cartels.

Back in 1999, when Markopolos calculated that based on how much money the secretive Madoff was taking in, he should have been running the world’s largest hedge fund managing and actively trading as much as six billion dollars, and this was at a time when the best-known hedge funds had no more than two to three billion under management. No matter how hard Markopolos looked he couldn’t find traces of Madoff’s trading activity in the financial markets. That meant he really wasn’t doing much trading at all.

Justly pleased with this insight, Markopolos in 2000 wrote an eight-page report and took it to the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission (SEC), the federal agency that regulates the American banking and financial industries.

“I had given them the case on a silver platter and gift-wrapped it, too,” he said. The result? Nothing happened. Why? Markopolos guessed (correctly as it turned out) that the SEC was staffed with lawyers, not finance wizards. The SEC enforcement director he had met with simply didn’t understand what he was saying.

Not one to give up, Markopolos went back in 2001 this time with an 11-page report, containing even more evidence and asserting that Madoff had now sucked in $12 billion from investors. Again, nothing happened.

The report got kicked up the ladder to the SEC’s New York office, but its chief had ruled that since Madoff was not a registered investment advisor he, therefore, could not be conducting dishonest business as an investment advisor.

For the next four years, Markopolos and his small team of financial sleuths continued to investigate Madoff. In the interim, in 2001 the well-respected U.S. financial journal Barron’s picked up a disquieting report on Madoff’s business published by an obscure finance magazine. Yet nothing happened.

So, in 2005 Markopolos wrote yet another report, this one 21-pages long, and gave it to the SEC. Now he estimated that Madoff had nabbed as much as $50 billion from his pigeons.

For a year, the SEC did nothing. Then it actually sent agents to talk to Madoff. They suspected that he was lying to them but concluded that his misdeeds, whatever they were, simply “were not so serious as to warrant an enforcement action.”

In 2008, Markopolos tried again, and again the SEC did nothing. But later that year the markets crashed, and Madoff, unable to pay investors demanding their money, was exposed. In December 2008, his two sons, who worked for him, asked their father why he seemed so distressed. Madoff confessed to them. The sons called an attorney. The attorney called the SEC, and the next day Madoff was arrested.

Around this time, Markopolos started packing a .38 revolver. After all, he had helped bring down a man who was likely managing money for Moscow mobsters and South American cocaine cartel leaders.

As much as $65 billion vanished. The hardest hit were hundreds of philanthropies, charities, museums, and foundations around the world, as well as the Royal Bank of Scotland, the Japanese investment firm Nomura, Massachusetts Pension Reserves and wealthy individuals such as Holocaust survivor and author Elie Wiesel, real estate magnate and publisher Mort Zuckerman, the family of former New York Governor Eliot Switzer, and actor Kevin Bacon.

Madoff was sentenced to 150 year term in a federal penitentiary and died of natural causes at the age of 82 in 2021. Worst of all, perhaps, is that his eldest son hanged himself on the second anniversary of his arrest. His younger son died of cancer four years later. His wife refused to communicate with him.

Markopolos won acclaim for his dogged pursuit of Madoff, and he’s become a global fraud investigator. Before going in finance, Markopolos served in the Army, and today he says, “I came from an Army background, and the one thing I can say about the Army is that we don’t quit.”

The SEC protects investment companies, public companies, lawyers and accountants so they can fleece the public.

Just ask Countrywide how well Sarbanes-Oxley works.

Markopolos was an odd bird and his attempts to communicate with the SEC failed in part due to his unusual style. Perfectly correct but ineffective.